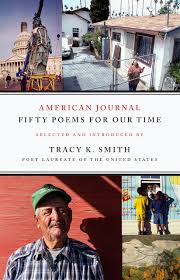

Traci K. Smith divides her anthology, American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time, into five sections: “The Small Town of My Youth,” “Something Shines Out From Every Darkness,” “Words Tangled in Debris,” “Here, the Sentence Will Be Respected,” and “One Singing Thing.”

Think about it. Each of those section titles would make a great prompt. Five stirrers for your daily writing cocktail. The first opens up memoir-like possibilities from your past and the town you grew up in.

The second offers a study in contrasts where you can use the rhetorical device of antithesis to explore one small phoenix that poked out from the ashes.

The third? Play with words and see how even tangled debris can take on significance.

Looking at the fourth title, I think of how the word “sentence” can be taken two ways, one if my diction and two if by the judge’s gavel.

And finally, the wonder, the shout, the ode of “one singing thing.”

So much for “I have no ideas.”

As an example of a poem Smith chose for the first section, “The Small Town of My Youth,” here is a poem by Oliver de la Paz:

In Defense of Small Towns

by Oliver de la Paz