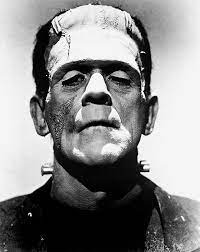

As writers, we are the sum of our reading parts. Or so the thinking goes. Like Frankenstein’s monster, we are pieced together by the books we read and all those styles, old and fresh, become parts of our body politic.

But it doesn’t always work that way. For instance, I have been reading more of Charles Simic’s poetry than anyone else’s of late. You know the feeling. You get in a groove for awhile, so you ride the wave and hang ten until you’re ready for some beach and a little rest under some other writer’s sun.

Simic is the epitome of simplicity. That’s a simplistic characterization, of course, but I mean his diction. His poems are mostly short, as are his lines. He favors end stops and many sentences travel no further than one or two lines, five max. It’s a style that invites imitation, like Hemingway’s in the prose world.

As a for instance, here’s a Simic poem I read just last night:

Nearest Nameless

by Charles Simic

So damn familiar

Most of the time,

I don’t even know you are here.

My life,

My portion of eternity,

A little shiver,

As if the chill of the grave

Is already

Catching up with me–

No matter.

Descartes smelled

Witches burning

While he sat thinking

Of a truth so obvious

We keep failing to see it.

I never knew it either

Till today.

When I heard a bird shriek:

The cat is coming,

And I felt myself tremble.

Gee, I wonder who Mr. Nearest Nameless is? Our old familiar friend, that’s what. The one carrying sharp objects (he has no respect for safety rules) while wearing a hood so he is as faceless as he is nameless.

The thing is, I also wrote a poem yesterday, to a friend who had lost a friend to the Nameless one. Was it the epitome of simplicity? Did it resound of Simic as you would expect?

Not quite. It was a single stanza poem, ten lines strong and all one sentence (commas working time and a half).

The moral of this story? It’s too easy to say that monkeys seeing will always become monkeys doing. Sometimes influences will push you in different directions. Sometimes, as a writer, you become the antithesis of the models you’ve been reading. It’s a bit like love, famous for bringing opposites together, where harmony can be found as each part finds a soothing escape from itself.

So much for “we hold these truths to be self-evident.” Yes, your writing may come under the spell of both classical masters and well-received contemporaries. But it may also make like the Sons of Liberty, tossing a little tea in the harbor in the name of artistic rebellion.

Whatever happens, accept it, because, whether you write with the tide or against it, you’re responding to it, and that’s what’s known in the writing world as inspiration.

So my thanks and appreciation go out to you, Charles. In short sentences or long, leggy poems or clipped. At least you have me writing!