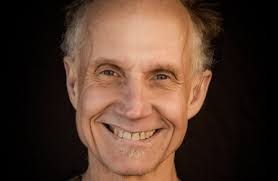

In his new, posthumous book, The Art of Voice, the gist of Tony Hoagland’s message can be found at the opening of Chapter 3, “The Sound of Intimacy: The Poem’s Connection with Its Audience.”

If you’ve been browbeaten by writing teachers and mentors who insist on economy at all costs, you might by surprised by his words:

“A successful poem is voiced into a living and compelling presence. The convincing representation of a speaker may be created by force, or intellectual subtlety, or companionability, or even by eccentricity, but it must initiate a bond of trust that incites further listening. That presence in voice is not always ‘intimate’ in a warm, ‘best friend’ kind of way, but the reader must be impressed that the speaker is a complex, interesting individual who is intriguingly committed to what she is saying, and how she is saying it.”

So far, so good. And it holds true for all writing, I think. Even blog posts. Do I have a voice here? With words as your only camera, can you “see” me by dint of diction alone? Hoagland continues:

“Such presence is only sometimes created by brevity. Many gurus on the craft of writing declare that a writer should ‘make every word count.’ Yet in poetry, often the charm of voice is more important than economy. After all, most of our daily interchanges don’t convey information in an economical manner. When we say ‘What’s up?’ or ‘Looks like rain,’ our speech isn’t really about conveying information, but about signaling to the listener that someone is present and accessible—open to conversation. They are gestures of presence. How about them Seahawks?”

I love that embedded little quote in this paragraph: “Often the charm of voice is more important than economy.” You can hear more than one poet craning her chin to the sky to shout, “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, I’m free at last!”

“All day, every day, those ‘uhs’ and ‘ers’ and ‘likes’ pepper and salt our spoken interchanges. These ‘inefficiencies’ of speech serve a purpose in building tone and voice; they ‘warm’ and humanize poetic speech; and they have their own prosodic contribution to make to poems. These interruptives, asides, idioms, rhetorical questions, declaratives, etc., float through our sentences like packing material, which in a sense they are—they pack and cushion and modulate the so-called ‘contents’ of our communications. And this technically ‘inessential language’ creates an atmosphere of connectedness, of relationality.”

From there, Hoagland goes on to provide examples in poetry via poems that live and breath voice. Without the “inessential” verbiage, they’d sink. Start weeding out “unnecessary language” in these works (á la writing workshop feedback from the learn’d astronomers) and you’d have a poem that fails.

Fancy that. The unfanciness of it all, I mean.

But, as I said in part one (yesterday’s post on Hoagland’s book), this is not license to be sloppy and wordy in your writing. It is permission to consider the word “essential” hiding in “inessential,” especially if voice is the craft that you are working on as a writer.

Not working on that craft? Maybe you should be. And maybe Hoagland’s parting-this-world words will help you in that cause.