Here is the last set of quotes I annotated in Mary Ruefle’s collection of essays, Madness, Rack, and Honey (recommended reading):

- “I remember, in college, trying to write a poem while I was stoned, and thinking it was the best thing I had ever written.

“I remember reading it in the morning, and throwing it out.

“I remember thinking, If W. S. Merwin could do it, why couldn’t I?

“I remember thinking, Because he is a god and I am a handmaiden with a broken urn.”

Comment: Whether it involves an altered state (like Arkansas, which elected Tom Cotton a Senator) or not, we all can identify with this. Certain authors, be they poets or not, just make it look so damn easy. (See Hemingway comma Ernie, for one).

- “I remember the year after college I was broke, and Bernard Malamud, who had been a teacher of mine, sent me a check for $25 and told me to buy food with it, and I went downtown and bought The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats.

Comment: A wise investment on Mary’s part, choosing food for thought over food for gut. And why didn’t I ever have a famous writer for a professor, one willing to send me checks, even? Instead, I had one that I handed a short story to for critique. He handed it back, saying, “I don’t have time for this.”

- “I remember the first time I realized the world we are born into is not the one we leave.

Comment: And the corollary — we do not leave as the same person, either. Strangers, they’d be.

- “They say there are no known facts about Shakespeare, because if it were his pen name, as many believe, then whom that bed was willed to is a moot point. Yet there is one hard cold clear fact about him, a fact that freezes the mind that dares to contemplate it: in the beginning William Shakespeare was a baby, and knew absolutely nothing. He couldn’t even speak.”

Comment: Finally, post-Disney, something Frozen we can embrace!

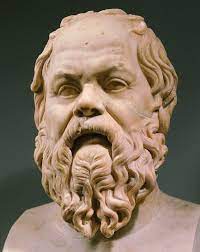

- “Socrates said the only true wisdom consists in knowing that you know nothing. It is his basic premise, one from which all his other thoughts come.”

Comment: If only we could find a politician with such basic premises. Instead, we have the makings of a book: The Arrogance and the Ignorance.

- “And I came to believe — call me delusional — that no living poet, none, could teach us a single thing about poetry for the simple fact that no living poet has a clue as to what he or she is doing, at least none I have talked to, and I have talked to quite a few. John Ashbery and Billy Collins can’t teach you a thing, for the simple fact that they are living. Why is that, I wondered. I mean I really wondered. I think it is because poets are people — no matter what camp they sleep in — who are obsessed with the one thing no one knows anything about. That would be death.”

Comment: And to follow through, living people know nothing about death. And to those who think my first two poetry collections are dark and depressing and overly fraught with the topic of death, I say, “Touché,” which is French for “So there!”

- “Ramakrishna said: Given a choice between going to heaven and hearing a lecture on heaven, people would choose a lecture.

“That is remarkably true, and remarkably sad, and the same remarkably true and sad thing can be said about poetry, here among us today.”

Comment: Get it? (Me either, but I like it!)

- “Short Lecture on Craft”

Comment: This the title of a short section in the book. I was so flattered to read this and learned so much about my name!

- “I love pretension. It is a mark of human earthly abstraction, whereas humility is a mark of human divine abstraction. I will have all of eternity in which to be humble, while I have but a few short years to be pretentious.”

Comment: Very cool. Just keep your pretensions under a bushel because, while they may be fun, they look butt-ugly to lookers-on.

- “On one piece of paper I had written ‘the difference between pantyhose and stockings’ and I had scanned the statement — with marks — and written ‘the beginnings of an iamb,’ which is bizarre because I can’t scan or recognize an iamb.”

Comment: Thank you. And please forward to all these Unlovely Rita, Meter Maid, poetry editors out there who take their beats so damn seriously and reject any poem not stinking of the Ivory Poetry Tower (ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM, ba-BUM).

- “Insanity is ‘doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results.’ That’s writing poetry, but hey, it’s also getting out of bed every morning.”

Comment: Meaning we should celebrate getting out of bed each day as a new poem. Think about it. The bed you rise from, like fingerprints, never quite looks the same. Write about it!

- “Now I will give you a piece of advice. I will tell you something that I absolutely believe you should do, and if you do not do it you will never be a writer. It is a certain truth.

“When your pencil is dull, sharpen it.

“And when your pencil is sharp, use it until it is dull again.”

Comment: A fitting end to all of these quotes, though I wonder what the pencil equivalent is to keyboards? Cleaning the damn thing? I mean, really. What could be more disgusting than a keyboard and its lettered-cracks?