In “The Whisper,” one of the last poems he wrote before death finally caught up with him, Jim Harrison wrote: “But birds/lead us outside where we belong./Around here all the gods live in trees.

If you don’t get outside as much as you should (and, chances are, you don’t), you can at least get the vicarious thrill (and I would say a convincing argument) by reading the 900-plus paged Jim Harrison Complete Poems.

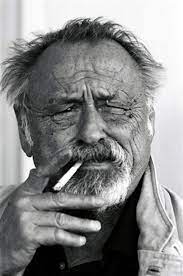

Though Harrison loved food, drink, and women, his first and most enduring love was the great outdoors. His poetry shows it. Among his gods, he shows greatest devotion to birds, fish, and dogs. And a keen eye for weather, land, and water. Harrison names things with a guide’s eye, and though any lifetime collection of poetry will be uneven, the reader can’t help but appreciate the voice, strong and friendly, that acts like Virgil guiding us through the book. Better yet, the voice only gets stronger as it wends its casual way to the end, too.

Many of the poems are built on memory. A good example is this tale of Harrison’s grandfather:

What He Said When I Was Eleven

August, a dense heat wave at the cabin

mixed with torrents of rain,

the two-tracks become miniature rivers.

In the Russian Orthodox Church

one does not talk to God, one sings.

This empty and sun-blasted land

has a voice rising in shimmers.

I did not sing in Moscow

but St. Basil’s in Leningrad raised

a quiet tune. But now seven worlds

away I hang the cazas-moscas

from the ceiling and catch seven flies

in the first hour, buzzing madly

against the stickiness. I’ve never seen

the scissor-tailed flycatcher, a favorite

bird of my youth, the worn Audubon

card pinned to the wall. When I miss

flies three times with the swatter

they go free for good. Fair is fair.

There is too much nature pressing against

the window as if it were a green night;

and the river swirling in glazed turbulence

is less friendly than ever before.

Forty years ago she called, Come home, come home,

It’s suppertime. I was fishing a fishless

cattle pond with a new three-dollar pole,

dreaming the dark blue ocean of pictures.

In the barn I threw down hay

while my Swede grandpa finished milking,

squirting the barn cat’s mouth with an udder.

I kissed the wet nose of my favorite cow,

drank a dipper of fresh warm milk

and carried two pails to the house,

scraping the manure off my feet

in the pump shed. She poured the milk

in the cream separator and I began cranking.

At supper the oilcloth was decorated

with worn pink roses. We ate cold herring,

also bluegills we had caught at daylight.

The fly-strip above the table idled in

the window’s breeze, a new fly in its death buzz.

Grandpa said, “We are all flies.”

That’s what he said forty years ago.

As he ages, Harrison grows more philosophical and tangos frankly with the more apparent subject of death. It only adds greater depth to his wisdom, nature being the perfect metaphor for the birth-death-birth cycle that so fascinated him.

Midnight Blues Planet

We’re marine organisms at the bottom of the ocean

of air. Everywhere esteemed nullities rule our days.

How ineluctably we travel from our preembryonic

state to so much dead meat on the ocean’s hard floor.

There is this song of ice in our hearts. Here we struggle

mightily to keep our breathing holes opened

from the lid of suffocation. We have misunderstood the stars.

Clocks make our lives a slow-motion frenzy. We can’t get

off the screen back into the world where we could live.

Every so often we hear the current of night music

from the gods who swim and fly as we once did.

Though he wrote novels, novellas, and essays, Harrison considered himself first and foremost a poet, making this lifetime collection that much more important to his legacy. Some compare him to Charles Bukowski (who had less of a connection with the natural world) and Ernest Hemingway (who lacked Harrison’s humor and gentle empathy), but neither comparison is fair. Harrison is Harrison, a one-eyed sage of the flower and fauna, river and ruin. Here is an example of his dark humor:

Poet Warning

He went to sea

in a thimble of poetry

without sail or oars

or anchor. What chance

do I have, he thought?

Hundreds of thousands

of moons have drowned out here

and there are no gravestones.

And here one of love for his wife on the occasion of their 50th anniversary. As is true with many of his works, he approaches subjects tangentially before hitting on this topic – the sort of thing a teacher of poetry would warn you against. Note, too, how he mines some of the same material as “What He Said When I Was Eleven,” only this time, being decades later, with a more mature approach.

Our Anniversary

I want to go back to the wretched old farm

on a cold November morning eating herring

on the oil tablecloth at daylight, the hard butter

in slivers and chunks on rye bread, gold-colored

homemade butter. Fill the woodbox, Jimmy.

Clots of cream in the coffee, hiss and crackle

of woodstove. Outside it’s been the hardest freeze

yet but the heels still break through into the earth.

A winter farm is dead and you want to head for the woods.

In the barn the smell of manure and still-green hay

hit the nose with the milk in the metal pails.

Grandpa is on the last of seven cows,

tugging their dicklike udders a squirt in the mouth

for the barn cat. My girlfriend loves another

and at twelve it’s as if all the trees have died.

Sixty years later seven hummingbirds at the feeder,

miniature cows in their stanchions sipping liquid sugar.

We are fifty years together. There are still trees.

Harrison is what is known as an “approachable” poet in that his style and topic matter is earthly. He is not one to tackle style or form. Rather, free verse is the lingua franca of his land. Don’t be fooled, however. His allusions have deep roots. Harrison read the best and used their names and experiences to leaven his own poetry. In these collected works, you will meet the likes of Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Frederico García Lorca, Apollinaire, Rimbaud, Virgil, W.C. Williams, René Char, Ikkyū, César Vallejo, Octavio Paz, Su Tung P’o, and, famously (thanks to his collection Letters to Yesenin), Sergei Yesenin.

Whether you read this hefty book cover-to-cover or use it as a side-dipper while reading others, you will feel, at the end, like you are saying farewell to a good friend and, in doing so, saying hello to your own approaching end. Thinking about his boyhood days, Harrison finishes the poem “Seven in the Woods” with these words: “It is the burden of life to be many ages/without seeing the end of time.” And in “The Present,” he meditates on birds yet again before ending on this note of a lifetime: “The cost of flight is landing.”

Alas, Jim Harrison has landed, but reading his collected work in the genre he considered most important, we can only give thanks for what he learned during his long, migratory flight.

***