The early risers. It’s a club that just as soon not meet, because what’s best about each morning is solitude—when a writer sends his convocation to the Muses. While the house still sleeps, I mean. And only the clock’s ticks can be heard. Or the dog’s breathing. Or the heat radiator’s pings.

Fitting music for writing, the early hours. One can’t help but believe that not only the household sleeps, but the world, for part of the magic of writing in the dark before dawn is the deliberate deception that you are the only one awake in the world. A childish delusion, then. Indoor light reflects your face in the dark window pane, and taking the dog outside reveals only a world with birds on the verge, raccoons on the move, and, weather depending, peepers singing (warm world) and owls whooing (cold, mysterious world).

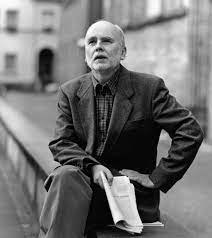

We are the perfect audience for Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s “The Early Hours,” a poem as much about writing as not writing (or, how writing is often hidden in the act of not yet writing). Paradoxical? Here’s the poem:

“The Early Hours”

Adam Zagajewski

The early hours of morning: you still aren’t writing

(rather, you aren’t even trying), you just read lazily.

Everything is idle, quiet, full, as if

it were a gift from the muse of sluggishness,

just as earlier, in childhood, on vacation, when a colored

map was slowly scrutinized before a trip, a map

promising so much, deep ponds in the forest

like glittering butterfly eyes, mountain meadows drowning in

sharp grass;

or the moment before sleep, when no dreams have appeared,

but they whisper their approach from all parts of the world,

their march, their pilgrimage, their vigil at the sickbed

(grown sick of wakefulness), and the quickening among medieval

figures

compressed in endless stasis over the cathedral;

the early hours of morning, silence

—you still aren’t writing,

you still understand so much.

Joy is close.

A muse of sluggishness? I missed him (and am convinced it’s a “him”) in Greek mythology studies but understand his presence, once announced. Then, the two metaphors, one about a love of maps formed in childhood, the other about that odd moment before sleep, the one where “no dreams have appeared,/but they whisper their approach from all parts of the world.”

Perhaps the biggest pay-off to the poem is how it refuses to acknowledge so-called “writer’s block.” Pre-writing, after all, requires NOT writing. Thinking. Dreaming. Creating and recreating the groundwork for poetry. Until, you can’t help but admit, “Joy is close.”

And that, for this poem’s particular trajectory, is the perfect closing.