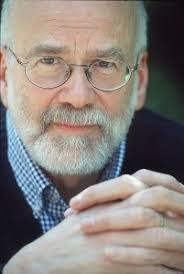

Earlier this week, I wrote a post about line breaks from Diane Lockward’s book, The Crafty Poet, sharing Wesley McNair’s (pictured above) first five tips on where to break your poems’ lines. Today we have the remaining five:

#6. Break so your reader sees how to say your poem.

#7. But don’t forget the wordlessness around the poem, which can be made articulate by a line break or by an artful arrangement of lines.

#8. Break mainly on nouns, verbs, and the words that describe them; they carry the sentence’s essential meaning.

#9. In your line breaking imitate the stresses of meditation and feeling, which are present in every earnest and intimate conversation and are the true source of the line break.

#10. Believe these tips and don’t believe them. Let the feeling life of your poem be the final authority.

Very cool how the final tip becomes a disclaimer pointing back to James Tate’s quote (shared yesterday) saying, basically, “Whatever the hell. It’s your poem!”

And #9 above, by using the words “meditation” and “feeling,” brings us back to the cryptic quote about lines being Buddha and sentences being Socrates. East is East and West is West and never Mark Twain shall meet, I think my English teacher told us. (Though that may be apocryphal like a lot of things she said.)

Look back, too, on #7, which gives a shout out to negative space, the final frontier. Too many of us forget that WHITE NOTHINGNESS is a part of every poem we write. It is agreeably malleable, willing to assume any shape our words, lines, and stanzas afford it.

As for me, I lean on #6 the most. I read my poems aloud for the musicality, the rhythm, the beats, the pauses. How natural does it sound? Am I throwing emphasis around the room with no regard for lamps and other fragile items? That would be good for the poem, even if it means a little clean up afterwards.

McNair’s advice is Everyman’s version of line breaking. Trust me when I say you can read scholarly works even on supposedly “free verse” which advocate all manner of “un-free” design in your freedom.

There’s fancy names for that, too. Ten dollar words you pick up off academic floors. But I’m not going there. One, because I do not have time; and two, because it’s too early in the morning to hurt my brain.

I’ll leave well enough alone, then, and wish you all a Ruby Tuesday….