Paul Muldoon (ex-poetry editor of some magazine or other called The New Yorker) has thoughts about young poets (age 9 to 99). He says their undoing comes when they think they know what they’re doing. If this happens, he says, they’ll most likely “disimprove.”

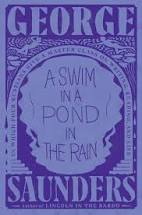

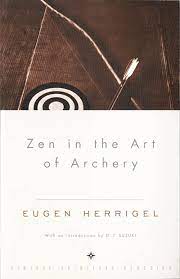

How do they reverse this trend (or improve from the get-go)? Muldoon’s advice, which he admits elicits head-scratching, is that they read Eugen Herrigel’s cult classic Zen in the Art of Archery. You have to allow yourself to go to a place of “innocence and ignorance,” to forget yourself, to give yourself over to a certain mysterious “it.”

If that sounds like something the too-busy-with-wonder-to-become-vain child you once were would be very good at, you’re right. I imagine, then, that there are no answers in books on how to write poetry or in poetry critiques or in the very expensive letters “M,” “F” and “A.”

I imagine, instead, that poets need only go out in the world and take it all in slowly and with an alien eye. Return to the word-of-the-year when you were a 5-year-old: “Why?”

Notice things about nature and people you stopped noticing long ago because you mistakenly assigned them to that category called “boring, everyday stuff.”

Muldoon’s point is that ignorance, a label we abhor and give to people we have little respect for, can be a good thing for poets. Why? Because in some respects little kids are ignorant, but in a receptive and innocent way.

Can adults reconnect with this inner child-poet and let poetry “be done to them” rather than trying too hard to do poetry themselves? You need only reread your favorite poems from the past and present to know that the answer is yes.

Oh. And Zen in the Art of Archery, of course.

Nota bene: Apparently, this goes for all genres of writing. As I picked up a copy of Max Porter’s Shy, I noted an interesting blurb from author George Saunder. It reminded me of this very topic. See if you agree:

“Max Porter is one of my favorite writers in the world. Why? Because he’s always asking the most important questions and then finding ways–through innovative structures and that inimitable voice–of answering those questions soulfully, with his full attention, in ways that make the world seem stranger and more dear (or more dear because stranger). He gives his readers, in other words, bursts of vision.”

Asks questions? Makes the world strange and dear? Sounds very Zen by way of Muldoon to me!

Here is the YouTube clip of a larger interview Muldoon offered.