Sometimes, when your mood shifts south, you need to pull it back. Sometimes reading certain poets helps with that–the task of settling yourself, of reeling your rogue moods back in.

For what is this mood, anyway, to think it can wrench you apart, then reunite you in its way at its bidding? Something worth resisting, that’s what. If not, it will make like a squatter and move in for good, taking over your spirit.

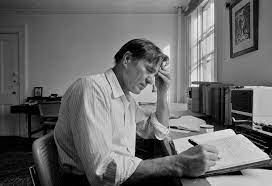

So today, being one of those days when my mood is getting ideas, I pulled out Galway Kinnell’s Mortal Acts, Mortal Words and reread two of his mortal poems. The simplicity of eating blackberries. The uncanniness of marital love. Cool, crisp, Vermont poetry. For when your mood’s thinking of going south and you need to show it who’s boss.

Blackberry Eating

by Galway Kinnell

I love to go out in late September

among the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries

to eat blackberries for breakfast,

the stalks very prickly, a penalty

they earn for knowing the black art

of blackberry making; and as I stand among them

lifting the stalks to my mouth, the ripest berries

fall almost unbidden to my tongue,

as words sometimes do, certain peculiar words

like strengths or squinched,

many-lettered, one-syllabled lumps,

which I squeeze, squinch open, and splurge well

in the silent, startled, icy, black language

of blackberry eating in late September.

After Making Love We Hear Footsteps

by Galway Kinnell