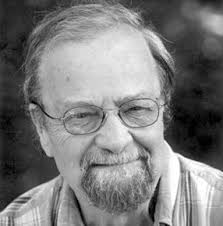

In poet Donald Hall’s second (and final, given his death in 2018) collection of essays, A Carnival of Losses: Notes Nearing Ninety, his prose style is concise and entertaining, proving compression (i.e. “the art of poetry”) has pay-offs for the essay writer, too.

For fans of poetry, two of the book’s four sections merit mention: “The Selected Poets of Donald Hall” (a series of reminisces about poets Hall met and interacted with over the years) and “Necropoetics” (an extended study of poems about death… something Hall was quite familiar with, having experienced the long and fateful death of his poet wife, Jane Kenyon).

Poets discussed in the “Selected Poets” section of the book include Theodore Roethke, Robert Creeley, Louis MacNeice, William Carlos Williams, John Holmes, Stephen Spender, Geoffrey Hill, James Dickey, Allen Tate, Edwin and Willa Muir, Kenneth Rexroth, Seamus Heaney, Joseph Brodsky, Richard Wilbur, E.E. Cummings, Tom Clark, and James Wright. Most of these “essays” are but a page or two long.

For a shorter one and a taste of Hall’s style, I give you his take on Kenneth Rexroth:

“New Directions published Kenneth Rexroth’s poems, and I read Rexroth with pleasure and excitement beginning in my twenties and thirties. Long poems and short, I admired him and learned from him, his diction and his three beats a line. His radio talks on California NPR made his opinions public. A dedicated anti-academic, he bragged, ‘I write like I talk.’ Whatever his taste or careful grammar, I kept on admiring his poems as he kept on being nasty about me and my eastern gang. I thought of a happy revenge. Frequently I wrote essays for the New York Times Book Review, so I asked its editor if he’d like an appreciation of Rexroth. Sincerely and passionately and with a devious motive, I wrote an essay to celebrate the poetry of Kenneth Rexroth. I imagined the consternation in California after my piece came out in the New York Times—the shock, the shame, possibly the reluctant pleasure. Mind you, he would not thank me. His publisher James Laughlin, mumbling out of the corner of his mouth, brought me a meager but appreciative word.”

Kill ’em with kindness, I always say. Especially when they’re playing tribal politics, something we watch with horror as it plays out in Swampington D.C. and thus, as poets, something we should know better than to repeat in our own little microcosm of intrigues and jealousies.

The reminisce about Allen Tate is quick but quick-witted, showing Hall’s signature sense of humor:

“My recollections of some poets are brief. Allen Tate always looked grumpy.”

The Tate page is so white, it is reminiscent of Basho and jumping frogs. A haiku, then, to the fifth of Snow White’s dwarfs, Grumpy:

Sp

las

h!

God has this little addiction. It’s called irony. Like O. Henry (only with more staying power), She can’t help herself when it comes to trick endings, little twists, wry surprises. Big G, they call her. Big “Gotcha!”

God has this little addiction. It’s called irony. Like O. Henry (only with more staying power), She can’t help herself when it comes to trick endings, little twists, wry surprises. Big G, they call her. Big “Gotcha!”