It is said that love and death are the two great themes of literature and, to some, reincarnation appears to be a convenient escape hatch for the latter. For Buddhists and Hindus, however, reincarnation isn’t as rosy a concept as it might first look.

From an Eastern perspective, it has historically meant another slog through pain, illness, old age, and death – perhaps in different form – while working on your karma in a quest to end the cycle. This final escape goes by various names – moksha, enlightenment, nirvana – but, to Westerners, second (and third, and fourth) chances all sound rather heavenly, much like having St. Peter and the Pearly Gates in your rearview mirror.

You know: Self, 1. Death, 0.

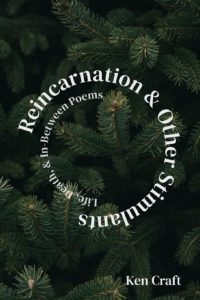

My third collection of poems – Reincarnation & Other Stimulants: Life, Death, and In-Between Poems – delves into this east-west ambivalence. It happened only because the poems gathered enough force and numbers to demand some organizing principle, and reincarnation came to the fore. The first poems were brought on by adversity — a sudden onslaught of bad news bedeviling me and people I knew and loved. On the Internet, I learned, we are not alone. Those who suffer chronic pain every day, for instance, may feel singled out (“Why me?”) but are decidedly not.

In a 2019 study, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimated that, worldwide, 20.4% of people suffer from some form of physical pain on a daily basis — and this doesn’t even consider those suffering from the psychological pain of despair and depression. Scarier still for these individuals? No matter how bad things are, there’s always someone who is enduring even worse.

The darkness of yin seeks out the lightness of yang, however. The questioning poems I was writing began to seek out answers for their own good. If the future of the body looks bleak and all too mortal, my writing seemed to be telling me, then perhaps it’s time to look through the lens of the spirit.

When I stepped back, I realized that poems I was writing were pairing off — opposites circling each other, craving each other, sharing each other. Poems of youth and old age, disease and health, sadness and joy, self and no-self, vanity and modesty.

Despite the Buddhist themes, this is not a Buddhist book per se. Nor do I consider myself an expert on the matter. Rather I borrow freely from Christianity (memento mori) and Buddhism (reincarnation) alike.

Loosely speaking, these poems are about me, people I’ve read about, characters I’ve made up. And it is not about people alone. You’ll find poems about the four seasons, old dogs, stranded cats, nesting birds, New England weather, and riprap (rock on!). There are even cameos starring Mark Twain, Henry David Thoreau, Frank O’Hara, Hamlet, and Emily Dickinson — some of my favorite people.

My hope, through all these pasts, presents, and futures, is that there will be something both novel and familiar for every reader. My other? That, like me, readers will agree that lightness and humor have a place in most any subject matter — even the required do-overs and karma overhauls we call “reincarnation.”