Vacation. For students, its special meaning lies in summer, the granddaddy of all vacations. For adults, however, it’s more narrow. Most full-time workers enjoy but 2 to 4 weeks of paid vacation each year. Compared to the nine-week wonder of childhood, slim provisions indeed.

Conjuring vacations of your childhood is sure to bring back a host of disparate memories. You’ll remember some close to home. You’ll recall a few long-distance car rides. And, if you’re lucky, you might reminisce about a certain long flight to some exotic location.

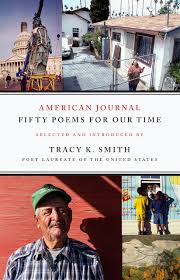

As fodder for writing, vacations are fertile ground. Water figures largely. Melville-like, we are drawn to the sea (it says so in Moby-Dick, after all). And E.B. White-like, we are drawn to the lakes (check out his beautiful essay, “Once More to the Lake”).

Marge Piercy uses lake vacations for material in her aptly-titled poem below. You can, too, by writing down the memories and the imagery that come to mind when you think of a childhood vacation. Once that’s done, you reach the “If you write it, they will come” phase, wherein metaphors come marching out of the water to give your draft some substance.

Here’s inspiration, Piercy’s last draft:

The Rented Lakes of My Childhood

Marge Piercy

I remember the lakes of my Michigan

childhood. Here they are called ponds.

Lakes belonged to summer, two-week

vacations that my father was granted by

Westinghouse when we rented some cabin.

Never mind the dishes with spiderweb

cracks, the crooked aluminum sauce

pans, the crusted black frying pans.

Never mind the mattresses shaped

like the letter V. Old jangling springs.

Moldy bathrooms. Low ceilings

that leaked. The lakes were mysteries

of sand and filmy weeds and minnows

flickering through my fingers. I rowed

into freedom. Alone on the water

that freckled into small ripples,

that raised its hackles in storms,

that lay glassy at twilight reflecting

the sunset then sucking up the dark,

I was unobserved as the quiet doe

coming with her fauns to drink

on the opposite shore. I let the row-

boat drift as the current pleased, lying

faceup like a photographer’s plate

the rising moon turned to a ghost.

And though the voices called me

back to the rented space we shared

I was sure I left my real self there—

a tiny black pupil in the immense

eye of a silver pool of silence.

I’m sure the Michigan lakes of Piercy lore are the same as the New Hampshire and Maine lakes of Craft lore. Lake or ocean, water is unique yet universal, a perfect brew for the inspiration-sipping writer.

Notice the imagery Piercy uses in stanzas 2 through 5, some of them indoor images, others outdoor. Notice, too, how it sets up the grand finale at the end. Like Fourth of July fireworks, endings often riff off concrete goods to offer an abstract bang. Here it comes in the form of metaphor, the narrator as a pupil (double meaning!) in the “eye of a silver pool of silence.”

So nice. So lake-like. A meditation compliments of the silently-lovely past.