From an early age, we are attuned to our special day, our birthday. We remember nothing of that perilous journey, of course, but our mothers will be happy to fill in all the missing details.

Over time, birthdays devolve into a familiar ritual of well-wishes, birthday gifts, and a fiery cake accompanied by a monotonous ditty. They also become reminders of the approaching other.

Think about it. Each year we lap another special day on the calendar, our birth date’s dark cousin (a. k. a. “the other”). Each year it smiles as we pass, nodding its head in that knowing way. This would be that patient trickster known as our death day.

After both are revealed, commemorating one special day over another can be a problem. The Kennedy family, for instance, would prefer that people not remember President John Fitzgerald Kennedy by the date of his assassination: November 22nd. They’d prefer people celebrate JFK’s life on his birthdate: May 29th. Unfortunately, people of an age (read: “old”) only think of the man on 11-22 because of ’63.

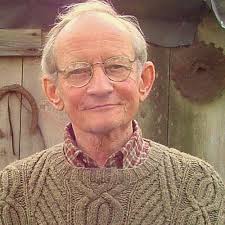

W. S. Merwin wrote a poem about the special day allotted to each of us — the one we choose to ignore. It is called, appropriately enough, “For the Anniversary of My Death.”

For the Anniversary of My Death

W. S. Merwin

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveller

Like the beam of a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

The first stanza is the living speaker, the second the speaker familiar with his formerly secret “deathday.” Stanza one offers some alliteration (“will wave” and “Tireless traveller”) as well as a rather oxymoronic contrast via simile: “Like the beam of a lightless star.”

I like how silence is depicted as a tireless traveller happy to never break its silence for eternity. If you’ve ever been frustrated by the dead’s refusal to yield up their secrets, you can identify.

In the second stanza, we get the wonderful metaphor of life as a “strange garment,” which makes sense given we exist for an eternity before birth and will exist again for an eternity after death. Clearly non-existence is the more familiar of garments.

As for life, it’s the mere blip between. In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius, a man attuned to his approaching secret day, pounds away at this fact of death (you thought I was going to say “life”?).

Merwin remains in the abstract with the “love of one women” and “the shamelessness of men” (something news readers and students of history can relate to). Then he shifts to the concrete with the last three lines.

Here we have three days of rain. Here we have a wren singing and “the falling cease / And bowing not knowing to what.” The word “falling” is nifty in that it ostensibly refers to the aforementioned rain but works just as well for the more Biblical falling of man. You know, the broken contract, wherein Adam & Eve lost their franchise, The Garden of Eden, and got stuck with this problematic death thing along with a host of other woes. Thanks, Adam & Eve.

As for “not knowing to what,” that brings us around to the great mystery again, the driving force behind all great literature: death. And yes, death will have its day.

Anyway, it’s a small outing for Merwin written in his characteristic, no-punctuation style, but I like how it reminds us of the thing we prefer to ignore, especially in modern day. Death was more a part of living in olden times. People were waked in the living room (ironically) of their homes, then buried by family.

Now the dying are hustled out of sight into nursing homes and hospitals. Funeral parlors are paid outrageous sums to take care of everything so the living can continue to pretend that they are immortal, even though they logically know they are not.

Birthday, Deathday. We should all wish ourselves a happy one of each and remind ourselves we’ll be blowing out the candles for good come “the other.”