Americans move a lot. Often it is jobs that uproot them and carry them, like seeds in the wind, to new pastures. Sometimes family concerns are the cause. Retirement, too, is often the driver once you’ve loaded all your earthly goods (and there are far too many) onto the cargo space of a moving truck.

When I was young and naive, I thought moving was a way to leave your troubles behind. If you hoped for a new life as a new person, I figured, you need only change your zip code.

Since then I’ve learned the lie in that theory. You can’t leave yourself behind. And you certainly can’t change who you are as a person like the flip of a switch. There’s hard-wiring to be reckoned with. There’s the lifetime experiences that resist the beguiling idea of a tabula rasa.

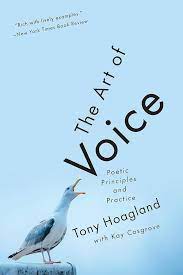

These thoughts rose to the surface when I read Howard Nemerov’s poem below. It’s a neat mix of concrete images and abstract thought, the artful blending that leads to the heart of any successful poem. Let’s take a ride with him:

Going Away

Howard Nemerov

Now as the year turns toward its darkness

the car is packed, and time come to start

driving west. We have lived here

for many years and been more or less content;

now we are going away. That is how

things happen, and how into new places,

among other people, we shall carry

our lives with their peculiar memories

both happy and unhappy but either way

touched with a strange tonality

of what is gone but inalienable, the clear

and level light of a late afternoon

out on the terrace, looking to the mountains,

drinking with friends. Voices and laughter

lifted in still air, in a light

that seemed to paralyze time.

We have had kindness here, and some

unkindness; now we are going on.

Though we are young enough still

And militant enough to be resolved,

Keeping our faces to the front, there is

A moment, after saying all farewells,

when we taste the dry and bitter dust

of everything that we have said and done

for many years, and our mouths are dumb,

and the easy tears will not do. Soon

the north wind will shake the leaves,

the leaves will fall. It may be

never again that we shall see them,

the strangers who stand on the steps,

smiling and waving, before the screen doors

of their suddenly forbidden houses.

Though much of the poem deals with inner thoughts, hopes, dreams, pleasant memories and bitter doubts, the end takes us to another truth: those we leave behind. It seems often that friends from one location become strangers once we’ve touched down in another. This despite our pledges to stay in touch, to visit, to remember.

Going away, then, often pulls us toward the blank promise of tabula rasa whether we wish it to or not.

And the north wind shakes the leaves….