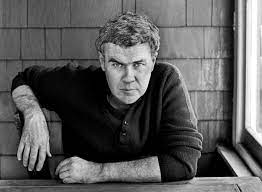

George Bilgere is the Ernest Hemingway of contemporary of poets. By that I don’t mean he shoots innocent lions in his free time or drinks like a marlin. I mean he makes writing look effortless. The complex simplicity of his work inspires in poets a most valuable sentiment: the good old “I can do that, too!” sentiment.

It’s great inspiration, this sentiment. And at least it gets you started. But then you realize it is not as simple as it seems. You start writing a poem, all psyched and sure you’re musing with the best of them, and then things go haywire. By line four. Before you even turn the bend of stanza one. How does he do it, you wonder?

Let’s sample some of his work and see for ourselves. The first, “Haywire,” gives us a distant, pre-industrial past through the eyes of a very old relative who happens to live in some back room of a childhood friend’s house. The distant past is served up as an agrarian utopia of sorts. Something that looks awfully good, especially if you lean sentimental.

“Haywire” by George Bilgere

When I was a kid,

there was always someone old

living with my friends,

a small, gray person

from another century

who stayed in a back room

with a Bible and a bed with silver rails.

They were from a time before the time

the world just plain went haywire,

and even though nothing

made sense to them anymore,

they’d gotten used to it,

and walked around smiling vaguely

at the aliens ruining the galaxy

on the color console television,

or the British invasion

growing from the sides of our heads

in little transistorized boxes.

In the front room, by the light of tv,

we were just starting to get stoned,

and the girls were helping us

help them out of their jeans,

while in the back room

someone very tired

closed her eyes and watched

a wheat field where a boy

whose name she can’t remember

is walking down a dusty road.

No sound

but the sound of crickets.

No satellites,

Or even headlights in the distance yet.

The next poem out-Billies Billy Collins. We see the poet in some European setting–some Masterpiece Theatre set from the BBC–doing what he shouldn’t be doing: a whole lot of nothing. Can anything win our hearts faster? We are all complicit. Hark:

“Once Again I Fail to Read an Important Novel” by George Bilgere

Instead, we sit together beside the fountain,

the important novel and I.

We are having coffee together

in that quiet first hour of the morning,

respecting each other’s silences

in the shadow of an important old building

in this small but significant European city.

All the characters can relax.

I’m giving them the day off.

For once they can forget about their problems—

desire, betrayal, the fatal denouement—

and just sit peacefully beside me.

In the afternoon,

at lunch near the cathedral,

and in the evening, after my lonely,

historical walk along the promenade,

the men and women, the children

and even the dogs

in the important, complicated novel

have nothing to fear from me.

We will sit quietly at the table

with a glass of cool red wine

and listen to the pigeons

questioning each other in the ancient corridors.

Our final sample shows that Bilgere, a playful and casual poet, can also play the poignant card when he needs to. I like that in a poet. It’s fine to be good at something, but it’s finer to prove that your portfolio is diversified. I can think of no better example than the following poem:

“The White Museum” by George Bilgere

My aunt was an organ donor

and so, the day she died,

her organs were harvested

for medical science.

I suppose there must be people

who list, under “Occupation,”

“Organ Harvester,” people for whom

it is always harvest season,

each death bringing its bounty.

They spend their days

loading wagonloads of kidneys,

whole cornucopias of corneas,

burlap sacks groaning with hearts and lungs

and the pale green sprouts of gall bladders,

and even, from time to time,

the weighty cauliflower of a brain.

And perhaps today,

as I sit in this café, watching the snow

and thinking about my aunt,

a young medical student somewhere

is moving through the white museum

of her brain, making his way slowly

from one great room to the next.

Here is the gallery of her girlhood,

with that great canvas depicting her father

holding her on his lap in the backyard

of their bungalow in St. Louis.

And here is a sketch of her

the summer after her mother died,

walking down a street in Berlin

when the broken city was itself

a museum. And here

is a small, vivid oil of the two of us

sitting in a café in London

arguing over the work of Constable

or Turner, or Francis Bacon

after a visit to the Tate.

I want you to know, as you sit there

with your microscope and your slides,

there’s no need to be reverent before these images.

That’s the last thing she would have wanted.

But do be respectful. Speak quietly.

No flash photography. Tell your friends

you saw something beautiful.

If you haven’t sampled this Ohio poet’s work, give him a go. Not only will it be an enjoyable read, it will inspire you to write. Because, after all, writing is easy. You can do it, too*!

(*Results may vary.)