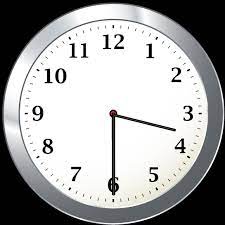

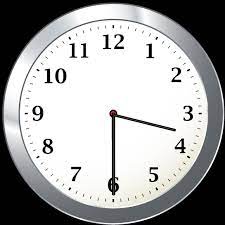

5:30 a.m. Rise and, first and foremost, get water boiling for a carafe of freshly-ground coffee. The first cup is the best. Always. But that never stopped a man from nursing numbers two and three.

6:00 a.m. Before checking the old inbox, repeat three times: “I need some good news today.” Click. See Merriam-Webster’s word of the day only. Well, at least it’s not bad news.

6:30 a.m. Begin writing. The focus has moved in the direction of journaling (the habit turns up stuff I can actually use later, I’ve discovered), but some mornings I’m still in the mood to tinker with poems from MS #4, even though it’s out a-courting some nine lucky publishers. I Know, You Know, and Don’t Know (the names of Mark Twain’s dogs, and you can look it up) that, when the manuscript is accepted, these revisions will be allowed through the pre-publication gates, so it is a worthwhile habit.

7:30 a.m. Timeout for breakfast. For me, it’s been the same drill lately. The night before, I take out an 8-ounce Bell jar, put a few raisins and a dash of cinnamon on the bottom, fill halfway with Old-Fashioned Oatmeal, then another round of raisins and cinnamon, followed by the second half of oatmeal, topped off with a third and final touch of raisins and cinnamon. Then I slowly pour in unsweetened almond milk (you could use the milk of your choice) until all the oats are just covered. Screw on the top, set in the fridge, and know that, by morning, it will be bliss, soft and cool. I follow up this cold oatmeal breakfast with a sliced orange.

8:00 a.m. More coffee, more writing. Some days it’s more deleting than writing. Some days I get to show off my addition skills. But more often I find myself tearing down yesterday’s progress, like a little bully boy at the beach who kicks other kids’ sandcastles down. The writer bully in me = eyes 24 hours wiser. The writer bully in me = nothing like what’s in the House comma White.

10:00 a.m. Take a reading break. Whatever the book of the moment may be (and right now, it’s Matthew Rohrer’s Army of Giants), usually, or sometimes I go to the two “ongoing” reads when I’m in the mood for them: The Complete Emily Dickinson (her poems may be short, but her production was immense) and Thoreau’s Journals (I like to match today’s date with a similar month and day in his journal, equally immense).

11:00 a.m. If it’s not raining, I make a short drive to the beach, where I get out and walk four miles. At the beach, everything is as it ever was: the surf, the sand, the seagulls and all the other S’s. They have no clue what “demagoguery” or “oligarchy” means. Nor do they care to. I can learn from cheek like that. I get a lot of “writing” done while I walk, too, thinking about that morning’s writing and where it went wrong or could go “righter.” As I logged many years at the shoreline as a boy growing up, looking out at the shards of sunlight on the seas’ surface brings me back. From your eyes, without glancing at your body, you forget that you’ve aged because, damn, it all looks the same, just like the days when you were young and limber.

11:30 a.m. How is it I never gave white sharks a second thought all those years I swam in the ocean? Summers nowadays? It seems that’s all I think of while in the briny is being vigilant, being ready to do battle with the weapons at hand (read: none).

12:30 p.m. Home for lunch. These days, not much, because you cannot eat as much after half a century’s walking on this earth, for one, and because lunch is the least interesting of meals. For me, it’s typically a protein powder shake (vegetable source) with frozen organic strawberries and blueberries and a sliced apple thrown in. And please, don’t get on my case about the “organic” thing by calling me a “foodie” or a “yuppie” or whatever label people like to throw about in our label-addicted world. “Organic” predates the conventional, herbicide- and pesticide-laden fruits and veggies we eat now. “Organic” simply means REAL and CONVENTIONAL because it’s what your granny (or certainly great-granny) ate before all the chemical giants came to the fore in the era of WW II (in that sense, we all suffered the same fate as Germany and Japan). So “organic” means “real food,” straight and simple, the way it was from time immemorial. Got a problem with that?

2:00 p.m. Practice on-line French. I took cinq ans of French back in the day but recall precious little (or, as they say in Paris, “petite presciouse“). They say that this, along with learning a musical instrument, is your best hedge against Alzheimer’s. I try to do at least 30 minutes of practice de français une jour.

2:30 p.m. I think to myself: “Remember when people worried about Alzheimer’s? Remember when “going viral” was a good thing?” Then I stop thinking for a bit, at least in that direction. Safer that way.

3:00 p.m. Time for a 30-minute nap, though it’s not a sacred animal for me or an assured thing or even an everyday thing, necessarily. It all depends on how the old insomnia thing was acting the night before.

3:30 p.m. Afternoon coffee, about as late as I dare. This is a small leftover cup from the morning, so nowhere near as good, but still good, and still better than snacking on processed food (again, thank you WW II era). I do this while going through another hour or two of reading the book of the moment.

5:30 p.m. Supper. I’d make a lousy European or cosmopolitan sort, as those folks like to eat at 9 at night or so. Still, there is good news for early supper eaters like me. The later in the evening you eat, the more likely it is that calories become love handles and belly fat while you sleep. Unless, of course, you’re blessed with one of those metabolisms. You know, the ones where adults can eat like 14-year-old boys and still look like healthy sticks.

6:30 p.m. Used to be, I’d watch the nightly news at this hour, although this almost assuredly is harmful for the health circa 2025. On good days, then, I go straight to some pre-recorded, bubble-brained comedy. Of late, my wife’s taken a shining to Younger which is enjoying a second life on Netflix. And sometimes, movies. Back in the bad old days of Covid lockdowns, I learned to pace myself for movies again. Occasionally. Most are still too long, just like contemporary novels are too long (lacking editors willing and able to use the scissors of common sense). Previous to Covid, I mostly loathed the movies and television shows. You know. Like Holden Caulfield did. After the word “phonies,” he probably said, “I hate the movies” more than anything else.

8:30 p.m. Last check for “good news” in the inbox from editors fighting it out for the privilege of publishing my poems (and what a joyful cartoon image THAT is!). Why do these people take so long? Why do I continue to dream that, some day, some editor will happen to read the work I submitted via Submittable on the same day it arrives and JUMP on it before any other editor can? Blame the last thing out of Pandora’s Box. Anyway, after this delusion, I repair to the kitchen to make tomorrow morning’s Overnight Oatmeal (see 7:30 a.m. entry for, ahem, recipe)

9:00 p.m. To bed with the book of the moment. This usually lasts all of 20 minutes before I drop the book on my face, making a literary divot on the bridge of my nose.

2:30 a.m. If I’m lucky to get this far, the first wake up. If I’m really lucky, I’ll get back to sleep within 20 minutes, but if it goes longer than that, it usually drags out for 90 minutes at least, forcing me to witness that most unseemly of hours: 3 to 4 o’clock, the hour that inspired me to write these poems in my first book:

Insomnia

Ken Craft

Three is the loneliest number on a clock

when the night can’t save you.

No doubt it is the constellated tug,

a conspiracy of stars, the silent, primal

voice that whispers the uselessness,

that grinds greater gears,

that mocks the hubris of careful plans,

set alarms. Every blanketed life around you

sleeps safe and happy and secure

like nothing can touch them, like change

has made its exception, named it you,

and passed finally over the frosted roof.

3:30

Ken Craft

In the dark

from over the water, a rooster

celebrates my insomnia

5:30 a.m. Wake and sing the simple ditty by some obscure minstrels from long ago: “Woke up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head.” And a fine déjà vu to you, too, using something as dated as a comb.

May you all have a great “day in the life” of your own, especially if you made it this far. Hum a John, Paul, George and Ringo song, why don’t you.