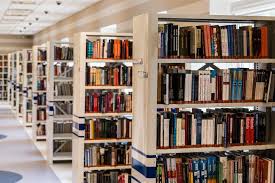

Most people judge a town by its school system. I judge it by its library.

How big is it? How versatile is its stock of books? How convenient are its hours, seven days a week?

Some towns I visit have beautiful fields for baseball, football, soccer. Some even have hockey arenas and sprawling golf courses. Lots of green that costs lots of green, but me, I like to see the green buying books, providing computers, hosting community events and readings. All at the town library.

A great library sends a signal: We care about the intellectual and artistic health of our citizens. Sports are great and have their place, but we open many, many doors to far away lands and new frontiers. We are the antidote to fake cries of fake news. We are, in fact, the enemy of fascism and anti-intellectualism.

Granted, no matter how vast and lovely, no library can cater to every taste. Thus, the inter-library loan system. Yes, I buy books and try to support writer royalties, but I’d quickly go under financially if I purchased every book I wanted to read.

Enter inter-library loan. Almost 90% of the books I seek can be found via this system. Place a hold, wait, and soon enough, the book arrives in port. Your home library.

Downsides? Not many. Some books get written in, and depending on the scribe, that can be an annoyance (though I have, on occasion, become as fascinated by the annotator as I have by the author).

Other books are marred with food and drink stains. What on earth causes people to eat chocolate, sticky buns, or cake and frosting while reading a book? Sugary fingerprints are not cool. Nor are dog-ears, the ghost of bookmarks past.

But these are minor inconveniences. Overall, there is no greater institution than a public library. It is deserving not only of your patronage, but your charity. Give a donation each year. Give everyone free access to the wonders of fiction, essays, plays, poetry, and every Dewey Decimal-ed piece of nonfiction out there. Doing so makes you a soldier of democracy, knowledge, light. There is no better way to fight the dark forces around us.

It’s a dangerous world, after all. Always has been and always will be. And the Fifth Rider of the Apocalypse? It’s Ignorance. Public libraries are the best ways to combat it—the swords to smote it down. An informed public is the enemy of authoritarian weeds, wherever they may sprout.

Patronize and support your town’s library, and if it’s suffering from want and neglect and lack of taxpayer dollars, create a committee to turn that intolerable situation around.

Sooner rather than too-later.