Prose poetry. Some people break out in hives at the term.

OK, how about narrative poetry written more in blocks than lines? (Some people who are cool with “prose poetry” say it ain’t prose poetry once you get more than two blocks, the blockheads.)

Good grief, man. Instead of looking at the hand, these folks need to look at the poetic license. Martin Espada is at home with political poetry too. Blatantly so. And it works.

Here are a pair from the book that should tempt you to dive in (apologies that line length limits at GR screw up the formatting):

Love is a Luminous Insect at the Window

for Lauren Marie Espada

July 13, 2019

The word love: there it is again, indestructible as an insect.

fly faster than the swatter, mosquito darting through the net.

How the word love chirps in every song, crickets keeping

city boy up all night. I wish I could fry and eat them.

How the word love buzzes in sonnet after sonnet. I am

the beekeeper who wakes from a nightmare of beehives.

To quote Durȧn, the Panamanian brawler who waved a glove

and walked away in the middle of a fight: No mȧs. No more.

Then I see you, watching the violinist, his eyes shut, the Russian

composer’s concerto in his head, white horsehair fraying on the bow,

and your face is bright with tears, and there it is again, the word love,

not a fly or a mosquito, not a cricket or a bee, but the Luna moth

we saw one night, luminous green wings knocking at the screen

on the window as if to say I have a week to live, let me in, and I do.

The Stoplight at the Corner Where Somebody Had to Die

They won’t put a stoplight on that corner till somebody dies, my father

would say. Somebody has to die. And my mother would always repeat:

Somebody has to die. One morning, I saw a boy from school facedown

in the street, there on the corner where somebody had to die. I saw

the blood streaming from his head, turning the black asphalt blacker.

He heard the bells from the ice cream truck and ran across the street,

somebody in the crowd said. The guy in the car never saw him.

And somebody in the crowd said: Yeah. The guy never saw him.

Later, I saw the boy in my gym class, standing in the corner of the gym.

Maybe he was a ghost, haunting the gym as I would sometimes haunt

the gym, standing in the corner, or maybe he wasn’t dead at all. They

never put the stoplight there, at the corner where somebody had to die,

where the guy in the car never saw him, where the boy heard the bells.

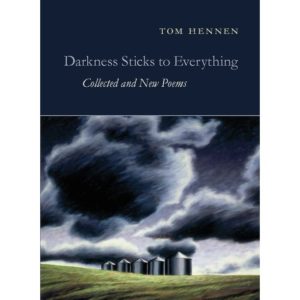

As the old saying goes: They don’t throw around National Book Awards (2021) for nothing.