Sometimes the image is everything, especially when it is an unexpected image, strange to the reader yet familiar—an oddly endearing combination.

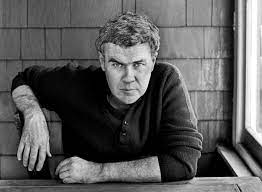

A good example of poet conjuring a bit of what used to be called “magical realism” is Jim Harrison in his poem, “Bridge.” In it he imagines a bridge to nowhere that extends unfinished over the “continent” we call the sea.

Imagine that vantage point on life! It’s what poet’s do, and it creates what John Gardner, in his book, The Art of Fiction, dubbed “the dream”:

“In any piece of fiction, the writer’s first job is to convince the reader that the events he recounts really happened, or to persuade the reader that they might have happened (given small changes in the laws of the universe), or to engage the reader’s interest in the patent absurdity of the lie.”

It’s the same effect you get at the movies or watching TV. The viewer willingly offers himself up as hostage, saying, “Take me, please, into this fictional dream so that I can forget the here and the now presently sitting on either side of me.”

This technique belongs as much to poets as to prose writers. As proof, let’s walk out onto Jim Harrison’s bridge:

Bridge

by Jim Harrison

Most of my life was spent

building a bridge out over the sea

though the sea was too wide.

I’m proud of the bridge

hanging in the pure sea air. Machado

came for a visit and we sat on the

end of the bridge, which was his idea.

Now that I’m old the work goes slowly.

Ever nearer death, I like it out here

high above the sea bundled

up for the arctic storms of late fall,

the resounding crash and moan of the sea,

the hundred-foot depth of the green troughs.

Sometimes the sea roars and howls like

the animal it is, a continent wide and alive.

What beauty in this the darkest music

over which you can hear the lightest music of human

behavior, the tender connection between men and galaxies.

So I sit on the edge, wagging my feet above

the abyss. Tonight the moon will be in my lap.

This is my job, to study the universe

from my bridge. I have the sky, the sea, the faint

green streak of Canadian forest on the far shore.

I love job descriptions like “to study the universe from my bridge.” It brightens an otherwise boring résumé like nothing else.

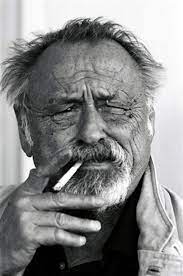

And the allusion to Brazilian writer Machado de Assis, I think, is a nod to the foamy waters between Realism and Romanticism. A gray area. Or green-trough area, maybe, where one can enjoy the endless feast of sky, sea, and “faint green streak of Canadian forest on the far shore.”

And, neatly enough, the “other shore” can be more than just Canadian forest. It could be “the other side” as in crossing the bar from life to death. The bridge, in that case, is our life’s work. Isn’t there time for rest, then? Relaxation? Pride in accomplishment? A few words with people we care about, just before the bridge finds its final footing on a distant shore?