Poets point the way to poets point the way to poets. This is a corollary of Gertrude Stein’s famous “Rose is a rose is a rose,” a.k.a. “Three ways to hit readers over the head with a dictionary.”

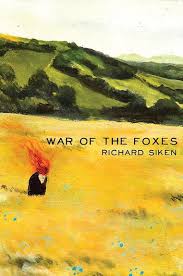

Anyway, while reading Victoria Chang’s Obit, I noted in her acknowledgments that one poem was inspired by a poem in Richard Siken’s collection, War of the Foxes. On Victoria’s recommendation, I found the book and started reading.

Still early on, but let’s look at a Siken poem that looks at painting in an interesting way. What if a man walks through a landscape? And what if we blur the line between artwork and life? We get something like this, which I offer as your “thought of the day.”

Oh. And don’t forget to tell people that you read this via Chang to Siken to Craft.

Landscape with Fruit Rot and Millipede

Richard Siken

I cut off my head and threw it in the sky. It turned

into birds. I called it thinking. The view from above—

untethered scrutiny. It helps to have an anchor

but your head is going somewhere anyway. It’s a matter

of willpower. O little birds, you flap around and

make a mess of the milk-blue sky—all these ghosts

come streaming down and sometimes I wish I had

something else. A redemptive imagination, for

example. The life of the mind is a disappointment,

but remember what stands for what. We deduce

backward into first causes—stone in the pond of things,

splash splash—or we throw ourselves into the future.

We all move forward anyway. Ripples in all directions.

What is a ghost? Something dead that seems to be

alive. Something dead that doesn’t know it’s dead.

A painting, for instance. An abstraction. Cut off your

head, kid. For all the good it’ll do ya. I glued my head back

on. All thoughts finish themselves eventually. I wish

it were true. Paint all the men you want but sooner or

later they go to ground and rot. The mind fights the

body and the body fights the land. It wants our bodies,

the landscape does, and everyone runs the risk of

being swallowed up. Can we love nature for what it

really is: predatory? We do not walk through a passive

landscape. The paint dries eventually. The bodies

decompose eventually. We collide with place, which

is another name for God, and limp away with a

permanent injury. Ask for a blessing? You can try,

but we will not remain unscathed. Flex your will

or abandon your will and let the world have its way

with you, or disappear and save everyone the bother

of a dark suit. Why live a life? Well, why are you

asking? I put on my best shirt because the painting

looked so bad. Color bleeds, so make it work for you.

Gravity pulls, so make it work for you. Rubbing

your feet at night or clutching your stomach in the

morning. It was illegible—no single line of sight,

too many angles of approach, smoke in the distance.

It made no sense. When you have nothing to say,

set something on fire. A blurry landscape is useless.