As has been the habit these past few years, winter has saved itself for March. Until Sunday night’s snowstorm (over a foot of snow, scorning the 4-8 inch predictions of our so-called “weathermen”), the winter was laughable, snow-wise. Cold? Yeah. But snow? Hardly enough to roll Frosty, taking him for all he’s worth.

March isn’t the most popular of months. Supposedly coming in like a lion and going out like a lamb, it is the advent of mud season (bad), red-winged blackbirds (good), and St. Patrick’s Day (if you like beer, very good).

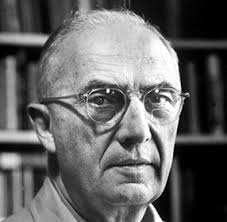

It also heralds the coming of spring (March 20th) in the northern hemisphere, giving poet Jim Harrison the right idea. He knew a sense of humor about March was essential to the season. As evidence, watch what he does at the end of this little poem:

Winter, Spring

by Jim Harrison

Winter is black and beige down here

from drought. Suddenly in March

there’s a good rain and in a couple

of weeks we are enveloped in green.

Green everywhere in the mesquites, oaks,

cottonwoods, the bowers of thick

willow bushes the warblers love

for reasons of food or the branches,

the tiny aphids they eat with relish.

Each year it is a surprise

that the world can turn green again.

It is the grandest surprise in life,

the birds coming back from the south to my open

arms, which they fly past, aiming at the feeders.

Clearly Jim wrote this about parts south of here. Note the specific nouns that matter most to a poem, in this case “mesquites,” “oaks,” “cottonwoods,” and the alliterative “willow bushes” and “warblers.” And like any hot dog, the aphids are eaten “with relish” (sorry, bad joke there).

Harrison uses a new stanza for a shift. The poem’s view pans back to a more philosophical scope. It goes from a particular March to “Each year it is a surprise…,” heaping praise on the earth’s regenerative powers, despite everything man does to it, despite the cynic’s sneaking suspicion that the cold may never let go.

Note how “the grandest surprise in life” is a phrase whose antecedent should be the world turning green but (curveball) turns out to be “the birds coming back from the south to my open / arms, which they fly past, aiming at the feeders.”

Oh, those selfish little birds. Guilty of gluttony, one of the Seven Deadly Sins. But anyone who has fed birds can appreciate the gentle joke here. The cliché, “she eats like a bird” to denote she hardly eats anything is laughably inappropriate. Birds eat many times their weight every day, and I’ve yet to see a chapter of Weight Watchers for Warblers open in any neighborhood near or far.

No, sir. Birds are ripped, as they say. Like charter members of Cross Fit. In great shape, as is Harrison’s sense of humor—a good thing to hold onto in such gloomy months as March.