As a lifetime dog guy, I know better than to say, “I hate cats,” because my wife and I have owned a few cats along the way and, I’ve discovered, you do get your occasional cat who acts like a dog. It would be more accurate, therefore, to say I am a dog guy who might like the rare cat that runs against the snooty cat grain.

Ditto poems and novels. There’s no black and white. I read novels for escapism and, often, the words. Every poet knows it when he or she is in a “poetic” novel. Heck with the roses. You stop and smell the imagery, the metaphors, the word choice.

As you can imagine, it can take a long time to read a poetic novel due to all this stopping and sniffing. But sometimes, like Cracker Jacks, there’s a surprise inside of garden-variety, read-for-pleasure novels, too.

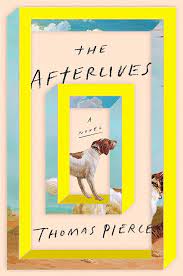

Once such book is the recently-released ghost tale, The Afterlives, by Thomas Pierce. After the required-by-law slow start, it picks up steam. Plot, mostly. Flip, flip, flip. This is what pages are for, most readers will assure you. But then, on p. 251, I came across this:

“She slept peacefully, her warm rump turned toward me, the blanket halfway up her leg, a burn mark on the sheet from the dryer. Everything felt significant, fleeting.

“I wanted to appreciate every aspect of this moment, to preserve it, to live in it forever. Annie’s light wheezing breath, the dance of the curtain across the AC vent on the floor, the clock’s red flashing colon that held the hours from collapsing into the minutes. I was in agony. I was crying. Sobbing, actually, face pressed to the pillow, the heat of my face rebounding off the fabric.”

No, it’s not Wallace Stevens or anything, but for one brief, shining moment, the speed-read-me novel of entertainment pauses to slow down its story, to catch a breath and drop a little imagery (Annie’s warm rump, the heat of his face on the pillow, the dancing curtain above the vent, the burn mark on the sheets).

I especially enjoyed the clock’s red flashing colon acting like a bulwark, trying to keep hours from collapsing into minutes. This novel is concerned, after all, with time and its partner in crime, death, with where we go after we die, and (the crowd-pleasing part) with ghosts who can’t quite cross the river, preferring to loiter among mortals who still haven’t figured out they’re not immortal. Thus, the clock imagery is especially apt to the moment.

So, yeah. As a reader you just never know when your escapist novel might gift you a poetic interlude. When you find it, take it for what it’s worth.

And, if your plot book gives you NO poetic moments, so be it. Make like Lewis and Clark and move on — over the western horizon to a book of poetry where you can breath deep the loyal doggy air for a bit. Variety, someone told me, is the spice of life….