It’s easy–too easy–to damn adjectives all to hell and preach the Word: Thou shalt scorn both adjectives and their brothers-in-crime, adverbs, when writing and revising poems. But the truth of the matter is less black and white and more perplexingly gray.

So assign your poet writers-to-be (or, more wisely, yourself) the task of writing poems without these modifiers all you want. It’s a great assignment, yes. It’s push-ups and jumping jacks before your physical endurance feat, too. But it ain’t going to be what most poems are: verse rife with adjectives that pay their freight.

Ah. As my boy Will (Shakespeare to you) once wrote: “There’s the rub.” When your revisionary eye turns to the task of revising, you can’t just take the delete button to every adjective you see.

Sure, it’s a great exercise in Zen extremes, but your poem will be left shivering in the cold of the white screen, begging like Oliver (“Alms for the poor?”), and wondering what draconian school YOU went to for your feral MFA.

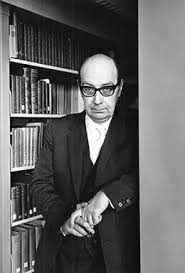

Let’s play a game and see how the pros do it. Below is a Philip Larkin poem that’s been messed with. Some of the adjectives are Phil’s and some are added by me, but all are in bold print.

See if you can identify the bad boys from the good. Don’t scroll down because the original appears below. Play the game first on the honor* system! (And imagine if I deleted the adjective “honor” from that request!)

Wild Oats (Not the Original, However)

by Philip Larkin

About twenty years ago

Two girls came in where I worked—

A bosomy English rose

And her studious friend in specs I could talk to.

Fresh faces in those days sparked

The whole shooting-match off, and I doubt

If ever one had like hers:

But it was the frowsy friend I took out,

And in seven years after that

Wrote over four hundred letters,

Gave a ten-guinea ring

I got back in the end, and met

At numerous cathedral cities

Unknown to the English clergy. I believe

I met beautiful twice. She was trying

Both times (so I thought) not to laugh.

Parting, after about five

Rehearsals, was an unstated agreement

That I was too selfish, withdrawn,

And easily bored to love.

Well, useful to get that learnt.

In my wallet are still two snaps

Of bosomy rose with svelte fur gloves on.

Unlucky charms, perhaps.

More adjectives than you’d expect, given the notorious nature of these parts of speech. Now take a look below to see how you did. How many Larkin adjectives got the axe in your version? How many Crafty ones passed muster and were left alone? Add them together to get your score. The higher the score, the more you need to ponder the point.

Phil’s original, then:

Wild Oats

by Philip Larkin

About twenty years ago

Two girls came in where I worked—

A bosomy English rose

And her friend in specs I could talk to.

Faces in those days sparked

The whole shooting-match off, and I doubt

If ever one had like hers:

But it was the friend I took out,

And in seven years after that

Wrote over four hundred letters,

Gave a ten-guinea ring

I got back in the end, and met

At numerous cathedral cities

Unknown to the clergy. I believe

I met beautiful twice. She was trying

Both times (so I thought) not to laugh.

Parting, after about five

Rehearsals, was an agreement

That I was too selfish, withdrawn,

And easily bored to love.

Well, useful to get that learnt.

In my wallet are still two snaps

Of bosomy rose with fur gloves on.

Unlucky charms, perhaps.

Of course, you are free to question even the greats. Is every adjective necessary in this poem? Does it depend on the poet? On the style? On the poem’s point?

Clear* as mud, as they say (in a useful-adjective kind of way).